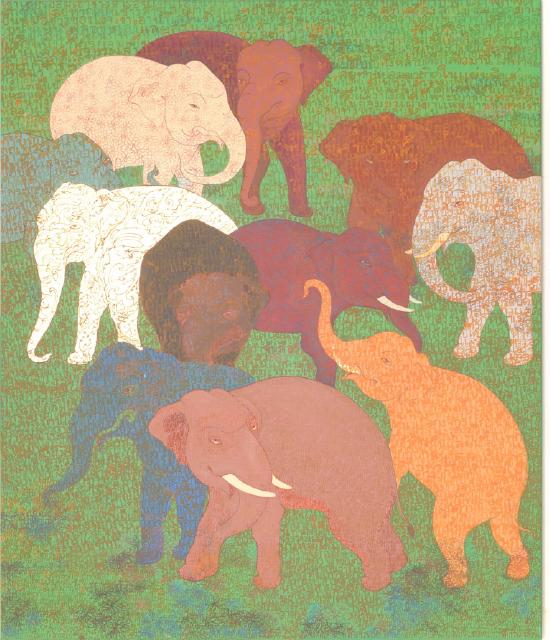

Phaptawan Suwannakudt: Not for Sure @ the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia for the 18th Biennale of Sydney

Artwork Details: 2009, acrylic on canvas, 120 x 100 cm

Courtesy the artist and Arc One Gallery, Melbourne

Photograph: Krzyzstof Osinski

On one of the smaller spaces on the 3rd floor of the MCA is Phaptawan Suwannakudt’s installation work Not For Sure. It is a curious title, based as it is on tentativeness and uncertainty. There are four wall pieces made from collage on open cardboard boxes and eight hanging scrolls suspended from the ceiling made from paper, architect-drafting film, silk and materials made from the natural fibres of Thai plants and herbs. Most of the surfaces have been inscribed with Thai texts and occasionally, for those who have come across her works before, the outlines of a familiar motif, an elephant or chang – which is Suwannakudt’s totem animal and nickname in Thai. The elephant of course is also the national animal of Thailand and is often represented in religious mural paintings. This is perhaps not a coincidence as she comes from the mural painting tradition, having been trained along with her sister by her father, the renowned traditional mural painter Paiboon Suwannakudt (also known as Tan Kudt). Significantly, although there have been some female artists who worked in the conservation of temples historically and there were a handful of female artists who worked in her father’s workshop including her sister Kapkaew Suwannakudt; Phaptawan Suwannakudt was the first one to lead a mural team for large scale mural projects. She did this for 15 years until her migration to Australia in 1996 at which point she shifted more towards individual canvases painted in the studio, and more recently 3 dimensional pieces and installation works. In this sense the motif represented here is simultaneously personal, familial and national; as well as pioneering and traditional.

Close-up view. Photograph: Krzysztof Osinski for Exhibition Footnotes.

She spoke about the collages on open cardboard boxes that have been mounted on the wall during her artist talk on July 29, saying that cardboard box resonated with her as a material because it was how she often shipped various personal belongings in between Thailand and Australia. There are four of these boxes on the wall and maybe representative of her family here– which is composed of herself, her husband John Clark and their two children Cantrachaaysaeng Clark (the moon sends its light) and Yenlemtarn Clark (the cool of the stream).

The palimpsest of text, layered on top of each other, sometimes peeled-off, sometimes on a translucent surface is undecipherable in our western context. She describes these as “metaphorical counter-conversations and act symbolically where stereotype is not permissible. The illegible text may challenge the human need to discover and to relate”. Which is perhaps an attempt to reverse the role many migrants finds themselves in, that is the onus is often on migrants to translate their experiences by any means necessary for it to be understood in the current context they find themselves in – even if at times these translations lapse into self-inflicted clichés, simplistic reductions, stereotypes and tropes. The hope of course is that there is enough curiosity in the mind of the viewer looking, to move towards a field that is foreign, minus the compensatory translations.

by the Theravada Buddhist Venerable Monk Ajahn Chah Subhaddo

This Buddhist influenced approach to art not as an end product but as an ongoing process and of being conscious of what your mind is doing is counter spectacle. And it has contradictory impulses to be both art and not art at the same time, “to do this, painting is not a painting of a subject, drawing is not a drawing of a subject, and making is not making of an object. It is rather the process of making things that you are reacting to”, she has said.The materialisation of an internal process can be subtle and it is partly dependent on each viewer looking whether this has been successfully conveyed or not. However this reception would partly depend also on how the viewer likes his or her art – brash and loud versus gentle and refined. Which is not to disparage brash and loud – they too have their place, but to acknowledge that her sensibility might not appeal to all people.

The opposite of not for sure is certainty and it’s an emotion that gives us confidence perhaps over-confidence in our assessment of things and in our outlook on life. Yet history is littered with things that we’ve gotten wrong, some incredibly badly; perhaps it’s time to look into tentativeness and uncertainty.Postscript:

I have based a lot of the information in this piece on the talk the artist gave on July 29 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia where her work was installed. I also referred to the artist for information on the tradition of Thai mural paintings, especially on the role of female artists in its history.

For other references on the artist please go to:

Rama Art 9:

Abstractions Exhibition at the Australian National University

The Elephant and the Journey MVA Thesis at SCA